Mary As Goddess: Mary Magdalen

The Written Record In seeking to unravel the mystery of the Marys in the New Testament, it is important to note at the outset that the Gospels were a later-recording of an oral history. In fact recent scholarship confirms that it is unlikely that any of the New Testament writers actually knew the historical Jesus (B,C,D *). The earliest New Testament records, Paul’s Epistles, were written circa 51-57 CE, and the other books were written nearer to the end of the century. Many of the Biblical accounts of Mother Mary and Mary Magdalen were written 50 years or more after the death of Jesus of Nazareth (B,C,D *). In addition, it is quite clear that the existing Bible today underwent additions, deletions, and translation changes over the centuries. In fact, the Bible as we know it today was not even compiled until the 4th Century CE, and no known manuscripts of the New Testament are older than the 4th Century. What exist are copies of copies (B,C,D *). However, many other Gospels were written that were not included in the official CHURCH canon. Among them are the Gnostic Gospels. Surviving copies of the Gnostic Gospels predate the surviving Biblical manuscripts by 200 years (A,B,C,D *). Why is it important to establish that the written record is based on oral history? What was once commonly understood as symbolic in the original version easily transmutes into the literal, and meanings are lost or change. While this is true of written records, it is especially true of oral histories (where it is impossible to examine the original version). It is important, therefore, to look to the cultural/historical context of the gospel stories when seeking to understand what the early Christians understood. The Goddess in Jerusalem Herod Antipas became ruler of the land through the ancient “Sacred Marriage” with the High Queen Mariamne, a priestess of the Triple Goddess Mari-Anna-Ishtar who was popularly worshiped at the time of Christ (B,C,D,E *). This Goddess was noted for her triple-towered temple or “magdala.” It is important to note that much of the imagery in the Gospels, especially regarding the Marys, corresponds to the worship of this Goddess Mari-Anna-Ishtar (B,C,D,E *). This will be explored in more detail in the following sections. Magdalen as the Bride of Christ

“I am the honored one and the scorned one. I am the whore and the holy one. I am the wife and the virgin. I am the mother and the daughter.” (A, p. 55-6) The Divine Mother and her Consort/Savior Son is a strong theme in World Goddess Myth, making Virgin Mary/Mary Magdalen a likely composite. As noted on the Virgin page, the title of Virgin was often bestowed upon sexually active Goddesses. Sacred Temple Prostitutes were often called Virgins (D). In addition, children of The Sacred Marriage, a ritual union of a temple priestess and a king willing to die for his people, were often called “virgin born” or “divine children,” just as Christ was (C). As noted on the Some feel that Mary the Mother and Mary the Lover were split into two characters–one good, the other evil–because women’s sexuality was demonized by the early orthodox church. (See Mother

Thirdly, Mary Magdalen is identified in Mark and Luke as the woman who was possessed by seven demons, which Yeshua cast out of her. The The last, and perhaps strongest, piece of evidence is the anointing of Yeshua with the sacred oil, an event which (uncharacteristically) was recorded in all four New Testament Gospels, pointing to its significance. The anointing of the Jesus’ head with oil (as described in Mark 14:3-4) is an unmistakable symbol of The Sacred Marriage, a ceremony performed by temple priestesses (B). Magdalen as the Bride of Christ Mary Magdalen was said to have been the Bride of Christ. Many of the Gnostic Gospels (revered early on in the Christian Church and later thrown out of the cannon) portray Mary Magdalen as Christ’s Most Beloved Disciple, reporting that Jesus often kissed her on the mouth and called her “Woman Who Knows All.” Other disciples went to her for Christ’s teachings after he died (A). She is portrayed as sitting at Jesus’ feet to listen to his teachings (Luke 10:38-42) and also as anointing his feet with oil and drying them with her hair (John 11:2, 12:3). Three of the New Testament Gospels report that Mary Magdalen was at the foot of the cross, and all four Gospels note she was present at the tomb. The Gospel of John notes that after the resurrection, Christ appeared to Mary Magdalen first. Mary Magdalen is mentioned in the New Testament more often by far that Mother Mary. In The Woman with the Alabaster Jar, Starbird presents a very strong case that Mary Magdalen was perceived by many Christians (up until the 14th or 15th Century) to be the Bride of Christ, who later bore his child. Just as the High Queen Mariamne was known to be a temple priestess, Starbird presents evidence that Mary Magdalen was a princess of Bethany. This Mary of Bethany (sister to Lazarus and Martha) was of the line of Benjamin. She was wedded to Yeshua, of the line of David, in order to fulfill the ancient prophecy that a Son of David would rule Jerusalem and a long period of peace would follow.

Others believe that Yeshua himself took part in the Sacred Marriage with Mary Magdalen, as the anointing foretold. The Sacred Marriage was a ceremony to renew the land, at times was followed by the death of the redeemer/king who was called upon to sacrifice his blood for the people. (See G) “Mari-Ishtar . . . anointed–or christened–her doomed god when he went into the underworld, whence he would rise again at her bidding. That is, she made him a Christ. Her priestess raised the lament for him when he died. . . . In the Epic of Gilgamesh, victims were told She ‘who anointed you with fragrant oil laments for you now’ ” (D, p. 615). Anointing the head with oil had Biblical precedent in announcing kingship and was well known to be symbolic of the Sacred Marriage ceremony (B,D *). When Mary anointed Yeshua’s head with sacred oil, he foretold his own death: “She has come beforehand to anoint my body for burial. . . . What this woman has done will be told as a memorial to her” (Mark 14:8-9). Immediately afterwards, Judas Iscariot (whose name means “zealot”) went out to betray him, for he understood that Jesus was going to sacrifice his life, not rule as king (B). A French legend recorded in the 4th Century CE says that Mary Magdalen (along with Lazarus and Martha) fled to the South of France (via Egypt) bearing “the earthen vessel that held the blood of Christ.” While legends of the Holy Grail took on a life of their own centuries later, merging with other legends, many believe that Mary Magdalen was herself the earthen vessel bearing Christ’s child, the sacred bloodline of David. Starbird provides convincing evidence that this was indeed what many early Christians, including the Cathars, believed. In the South of France, the Cult of the Magdalen flourished until it was all but wiped out in the Albigensian campaigns by the Roman Catholic church in the late 13th Century. (B,D,E,F *) The Song of Songs, the most popular love poem at the time of Christ and for centuries afterwards, was strongly associated with Mary Magdalen, believed to be the bride in the poem, and Yeshua the bridegroom. Attributed to Solomon, the Song of Songs has remained part of the official cannon, despite its unmistakably erotic imagery. The Roman Catholic church traditionally reads from the Song of Songs on Mary Magdalen’s feast day (B). MM as Hermit

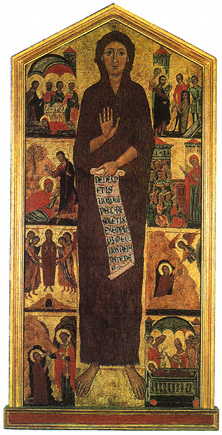

8 scenes from her life by the Magdalene Master c. 1280 Florence Galleria dell’Accademia

The Cult of the Magdalen, forced underground, is linked to the Cult of the Black Madonna, which thrived in France and elsewhere in Europe. There has been much speculation as to the origin of the Madonna’s blackness. One link is to Sarah “The Black Queen,” believed to be the child of Mary Magdalen, brought out of Egypt. The town of Les-Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in southern France still celebrates her festival (B). Other links are scriptural, such as to the bride in the Song of Songs: “I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem” (Song of Solomon 1:5, B,C *), or to the deposed Davidic princes of Jerusalem: “now their appearance is blacker than soot, they are unrecognized in the streets” (Lamentations 4:8, B). One of Mary Magdalen’s most prominent shrines, at Chartres, centered around a statue named “Our Lady Under The Earth” (B, p. 79). This also emphasizes her hidden aspect.

(Also see Our References By Elaine Pagels (B) by Margaret Starbird (C) By Marina Warner (D) By Barbara Walker (E) By Clysta Kinstler by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, Henry Lincoln (G) by Diane Wolkstein (H) By Elinor Gadon (I) by Lone Jensen ( * ) And numerous other sources |